|

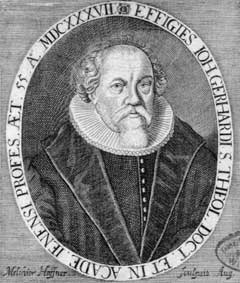

| Johann Gerhard, 17th-century German theologian |

[Prayer] is

a ladder by which we ascend to heaven, for prayer is nothing else than a

drawing near of the mind to God. It is a

shield of defence, because the soul that liveth daily in a spirit of prayer is

secure from the insults of devils.

Prayer is a faithful messenger we send to the throne of God, to call Him

to our aid in the time of need.[1]

That just

constitutes a sampling of the engaging poetic imagery Johann Gerhard pens in

his devotional books. Born in 1582 and

living until 1637, the German theologian studied in the age of Lutheran

Scholasticism following the publication of the Book of Concord, which he helped

support by way of his outstanding doctrinal literature, the Loci. However, alongside of this, he assisted in

building up the collection of short sacred contemplations accessible for

personal use. In this genre, he

idiomized a metaphorical style influential to later authors of the cultural

Pietist flavor. Overall, these

metaphorical devices of Gerhard’s devotional writings as a rule directly quote

Scripture or paraphrase it using accurate hermeneutics.

First

of all, extended metaphors typically influenced by Biblical parables encompass

substantial paragraphs, even in alternation.

Popularly, Gerhard likens the salvation story to a marriage relationship

between the soul and Christ, and weaves in many other familiar types as

well.

Jacob served

fourteen years to win Rachel for his wife, but Christ for nearly thirty years

endured hunger, thirst, cold, poverty…Samson went down and sought a wife from

among the Philistines, a people devoted to destruction, but the Son of God came

down from heaven to choose His

bride from among men condemned…Foul and defiled was His bride, but He anointed

her with the oil of His mercy and grace.[2]

Amongst other notable figures the author

features are the vine and branches, the robe of righteousness, the flood of

baptism, evening and morning, the oil of faith, and the Shepherd and sheep.

Next, Gerhard

often utilizes the technique of repeatedly comparing and contrasting two people

or objects, such as the sinner and the Savior, in order to make a point. Furthermore, this can be used for either a

Law comfort or Gospel promise. For

example, “If this be done in a green tree, what shall be done in a dry (Luke

23:31)? If this be done to the Just and Holy One, what shall be done to

sinners?”[3] On the other hand, in discussing the

blessings brought to the Christian by the Passion, Gerhard lists many points of

deference between their state and their Redeemer’s. Here is a mere sampling:

He willingly

submitted to be stripped of His garments, that He might restore to us the robe

of innocence, lost through our transgressions.

He was pierced with thorns,

that He

might heal our sin-pierced hearts. He

bore the burden of the cross, so that He might remove from us the awful burden

of eternal punishment.[4]

Third,

Gerhard uses analogies either drawn from plain understanding or explained by perspicuous

biblical passages in order to express a correct exegetical inference. In “Loving God Alone” from Sacred

Meditations, he supports from the conclusion that if God is perfect and

most loving as the Creator, one should reciprocate that love rather than to

other creatures.

Does not

that man do himself injury who loves anything beneath the dignity of his

nature? Our souls are far more noble

than any created thing because redeemed by the passion and death of God. Why then should we stoop to love the

creature?...Whatever we love, we love because of its power, its wisdom, or its

beauty. Now what is more powerful, what

is wiser, what is more beautiful, than God?[5]

In the “Prayer for Victory Over Temptations

and for Safe-Keeping from the Devil’s Plots,” Gerhard applies the scale of

Christ’s temptations to the weak believers’.

If he dared

to attempt to make himself commander of the heavenly army, will he keep himself

from me, a common soldier? If he did not

think twice to oppose the

very Head

(Matthew 4:3), is there any wonder that he attempts to destroy a weak member of

the mystical body?[6]

Fourth

of all, sometimes Gerhard brings out the simplicity of a truth by means of very

short sentences, frequently to compare and contrast, even directly citing

Scripture. “I despair of myself. In You, hope is repaired. Of myself, I fail. In You, I am restored. In me, there is anguish. In You, I find joy once again.”[7] In regard to the “Denial of Self”: It is better for me to be nothing in You and

receive Your everything than to be something in and of myself and have

nothing. Where I am not, there I am happier. My weakness longs to be strengthened by Your

might. My nothingness reaches for Your

strength.”[8]

In a “Thanksgiving

for Preservation” prayer, to bring out the truth that everything needed to

sustain life belongs to God, Gerhard assembles a chain of short sentences to

bring home the reality:

In You, I

bend and move my limbs. Without You, I

cannot participate in life and movement…The day belongs to You. The night belongs to You…Silver is

Yours. Gold is Yours.[9]

Lastly,

Gerhard views the Bible in light of the theology of the cross, and also

Christocentrically. Any conclusions he

draws are based on keeping the message of Christ’s atoning act central,

accentuating the Messianic typology already found in Scripture. To

ignore such clear signs would be an

exegetical crime, and would even render the interpretation more obscure.

In

the end, all of the abovementioned literary tools are utilized by Gerhard for a

poetic effect, organizational quality, interest, and finally as Scriptural

basis for his seemingly subjective ideas.

Though some may attribute his heavy usage of metaphors to the foreshadowing

of Pietism, they still fall in line with Lutheran orthodoxy in that most are

drawn from the Bible. In including types

and descriptive language, Gerhard does not introduce foreign doctrine or

misleading analogies that would suggest improper hermeneutics. Rather, they act as his paintbrush to color

biblical concepts, only serving to direct the appreciator towards the perfectly

designed model of Holy Scripture.

No comments:

Post a Comment